The need for aortic valve replacement was covered from the 1970s by open-heart surgery with extracorporeal circulation in which the sick valve was resected and replaced by an artificial valve stitched to the aortic fibrous ring. The first valves were metal and long-lasting but required lifelong anticoagulation. Then biological valves started to be implanted, especially in elderly patients, made of avascular swine or pericardial tissue, which required less antithrombotic medication.

The outcome was excellent with both types of valve as far as recovering valve function was concerned, but the surgeries involved opening the chest by sternotomy, stopping the heart with extracorporeal circulation and a long post-op process with possible complications, both infectious and derived from the extracorporeal circulation, renal failure and sternum dehiscences, especially in elderly patients in whom degenerative aortic stenosis is so prevalent.

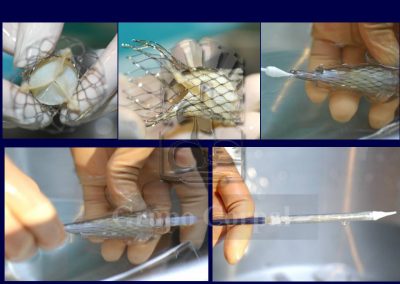

The percutaneous implantation (via puncture) of a biological aortic valve has been possible since 2005. It was initially applied to elderly patients with high surgical risk or who refused surgery. The outcomes were comparable to those of surgery, with a huge reduction in patient discomfort, in complications and in recovery time. Such interventions have gradually spread to low risk patients and percutaneous implantation is clearly on the rise.

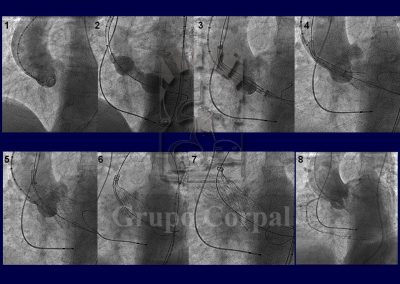

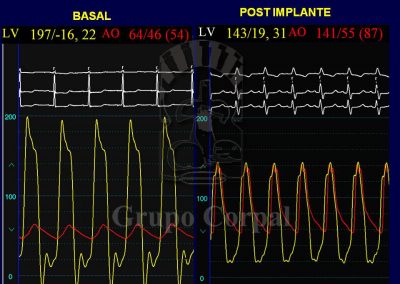

From a technical perspective, percutaneous implantation is simple and standard. It requires general anaesthesia and 2 artery (both femoral) and 2 venous punctures (1 femoral and 1 jugular). The jugular route is for the implantation of an electrode catheter in the right ventricle, which acts as a preventive pacemaker, as transient or definitive atrial-ventricular block occasionally onsets during implantation (15%). The 2 femoral artery routes help us to monitor systemic and ventricular pressure before, during and after the procedure, to evaluate the outcome. They also help us to angiographically select the appropriate puncture site to insert the cannula that carries the valve and small aortographies during implantation.

Although not essential, it is also advisable to monitor the implantation by transoesophageal ultrasound. After implantation, the outcome is evaluated both haemodynamically and angiographically and the point of insertion is closed by a Prostar device, verifying the outcome by contralateral angiography.

This procedure’s mortality rate in high risk patients is no more than 5%, less than that of valve replacement surgery. The most common complications include atrial-ventricular block, which could require a pacemaker, a degree of peri-valvular leakage, especially in highly calcified valves, and some problems associated to the femoral approach route.

All these complications can also be prevented and/or treated percutaneously, and they are rare in experienced teams. Some elderly patients, with considerable aortic atheromatosis, can also present stroke due to plaque release during implantation manoeuvres (1%). In our experience, a good outcome can be expected, with the resolution of the stenosis and no aortic regurgitation. Recovery is prompt, and discharge is usually 3 days after the procedure.

The age of percutaneous implantation is falling, as young patients are being given biological valves.