Arrhythmia is an altered heart rhythm. It can be a fast heartbeat (tachycardia) or a slow one (bradycardia).

It can arise at any time in life. Some cases are due to genetics but most are acquired. They can arise in healthy hearts or hearts with structural cardiopathies (myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathies, congenital cardiopathies, etc.).

Symptoms vary, and can include palpitations, dizziness, syncope (loss of consciousness), chest pain or sudden death, etc. They can also go unnoticed and be detected by chance when diagnostic tests are performed.

Arrhythmia can be paroxysmal (comes and goes in minutes or hours) or permanent (fully established).

Diagnostic techniques

It is diagnosed when there is an alteration in the heart’s electric activity. The first thing to do is to perform a cardiological study to rule out an associated cardiopathy.

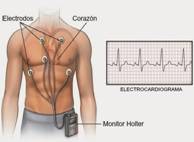

The ultimate diagnostic test is an electrocardiogram. It causes no discomfort for the patient, is quickly performed and the patient does not require hospitalisation. The main problem with this technique is that it records the heart’s electric activity at a given moment, and does not record an alteration if it does not occur at that time. To record an arrhythmia we use electrocardiograms recorded over days, weeks or even years, with what is called a HOLTER (figure 1). Usually the patient goes home with a Holter device that constantly records the activity of his or her heart for one or several days.

The Holter device that records years of electric activity, however, is implanted in a minimally invasive manner beneath the skin (subcutaneous) and is known as an implantable cardiac monitor (Figure 2). This technique is used for patients in whom a conventional electrocardiogram has not recorded anything of note, yet they still present severe clinical symptoms (loss of consciousness, severe palpitations, etc.). They are so small that they go unnoticed and they help us to monitor heart rhythm for years. If the patient presents symptoms, we can subsequently analyse the cause.

Once an arrhythmia is diagnosed, the cardiologists will advise about the different treatments available, which will depend on the disorder in question.

Treatments include drugs, pacemakers or defibrillators and/or techniques to definitively cure arrhythmia by ablation of the cause.

Drugs are usually the initial strategy and are commonly used. But they do not “cure” arrhythmia, but reverse episodes and/or reduce their number. They are not tolerated by all patients due to their side effects, so they are not very effective.

When arrhythmia attacks are frequent, poorly tolerated and/or not controlled by drugs, the recommendation is an electrophysiological study to evaluate the possibility of ablation.

Electrophysiological study

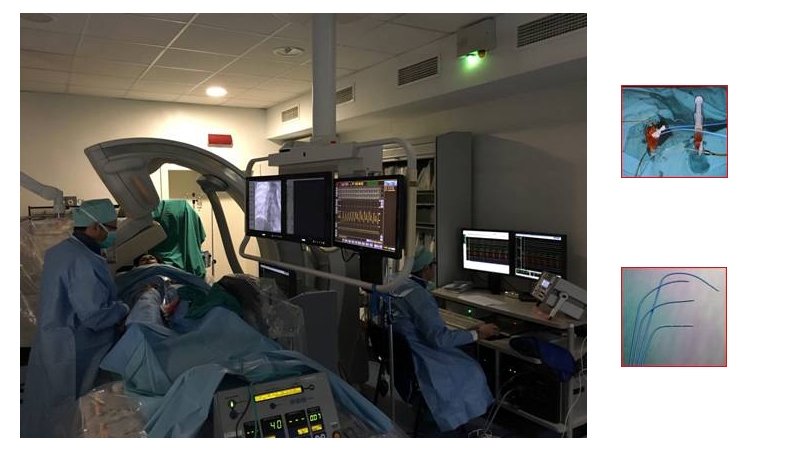

This is an invasive technique performed with local anaesthetic. It is actually catheterisation but with the objective of studying the heart’s electric activity. Electrode catheters are inserted through the groin. These catheters are wires that, located in different parts of the heart (atria, ventricles, atrial-ventricular ring, etc.), tell us about the heart’s electric activity normally and also during tachycardia. They also stimulate the heart to tell us whether the electric impulse follows the normal pathway or there are short circuits that alter its rhythm.

The patient is awake and collaborates during the study.

When we have identified the arrhythmia mechanism we can use catheters that apply radiofrequency (heat) or cold (cryo-ablation) to make these short circuits disappear. Arrhythmia is cured in 90-98% of cases, with few complications. The procedure can last from 30 minutes to several hours, depending on the location and the ease with which tachycardia is induced.

After the procedure, the patient rests for a few hours to prevent complications at the access site, and is usually discharged after 24 hours.

Tilt test

Syncope (loss of consciousness) is an acute situation difficult to diagnose, as the causes usually do not last for long and it is difficult to record what is happening. Patients with syncope should be examined by a cardiologist, who will perform different examinations in an attempt to reach a diagnosis. One of them is the tilt test, which aims to confirm syncope with a vasovagal cause. They are due to a neurovegetative disorder that significantly slows down the heart rate, or by hypotension, or both at the same time.

This patient is undergone as an outpatient and consists of constantly recording an electrocardiogram and the patient’s blood pressure while he or she lies on a gurney for 5 minutes. The gurney is then tilted by 70 degrees and left in this position for 20-30 minutes. If no symptoms present, a drug is administered in an attempt to trigger syncope. Blood pressure and heart rate are recorded for another 20 minutes. If the cause is vasovagal, the patient will present loss of consciousness secondary to hypotension, low heart rate or both. Even if the patient presents syncope, he or she can be discharged home after the test.

Wireless cardiac stimulation

A low heart rate can represent an important problem. The patient can present tiredness and dizziness. It can even be fatal if not correctly treated. These disorders often require treatment with external cardiac stimulation (pacemaker). These devices are implanted beneath the skin, and a wire is inserted through a vein to the heart’s cavities. It is a relatively simple technique performed under local anaesthetic. But it has some disadvantages, such as:

1) Aesthetics: although it is small, the skin that covers it juts out slightly, and shows a scar. The patient sometimes notices discomfort for some time.

2) Infections: as with any intervention, the “bag” that contains the pacemaker can become infected. This is not an easy complication to solve and the pacemaker often has to be removed.

3) Problems with the wire: the wire is occasionally damaged by contact with different structures, preventing the pacemaker from working properly. To prevent this, wireless stimulation has been developed, and looks very promising.

It consists of implanting a much smaller wireless pacemaker in the right ventricle.

It is performed under local anaesthetic, using the femoral vein, through which this small device (Figure) is taken to the tip of the right ventricle. After verifying that it is in the right position and working properly, the femoral introducer is removed and the patient is discharged 24 hours later. It is currently only available for cases requiring a single-chamber pacemaker, but the implantation of wireless two-chamber pacemakers is expected in the next few years.